By Kelly Brown, EdD and Deirdre Williams, EdD

This is the final article in a three-part series on equity in education. In the first article, we explored how leaders can begin to use equity to transform the school environment for every learner. In the second article, we shared how equity audits are used to collect the data that informs the process of removing programmatic barriers that impede full participation, access, and opportunity for all students to receive an equitable education.

What actions can the school leader do to develop a professional learning community that has a persistent and intentional focus on rigorous leading, teaching, and learning for everyone? Integral to school reform movements is the professional development of teachers to support school success (Thornburg & Mungai, 2011). In the previous articles, there was a discussion about equity and how school leaders can begin to move toward creating a school culture focused on equity (Williams & Brown, 2019; Brown & Williams, 2019). Teachers, however, are the most significant influence on student outcomes (Ronfeldt, Farmer, McQueen, & Grisson, 2015). Therefore, in order to achieve this audacious goal, teachers must be able to work effectively as a team and build a community where each teacher elevates their skill set and each child is lifted.

Successful and collegial collaborative cultures encourage teachers to participate in authentic interaction that includes openly sharing both successes and failures, and to possess the ability to respectfully and constructively give feedback on practices and procedures that promote self-reflection (Battersby & Verdi, 2015; Marzano, 2019). An effective model for professional development requires that all participants are involved in the process and outcomes. “This model entails diagnosing one’s own learning needs, as well as designing and implementing the change effort” (Futrell, Gomez, & Bedden, 2003). Inevitably, “schools can’t become better places for kids unless the adults learn” (Fahey & Ippolito, 2017). That said, there are a set of cultural and structural conditions that must be in place to optimize adult learning to improve student achievement (Mohr & Dichter, 2001). The fundamental conclusion from experience is teachers learn best when they are able to share their practice with team members, become reflective, and build both a common understanding and shared belief about the adult behaviors that foster positive student outcomes (Bryk, 2010).

It is imperative school leaders begin to develop a culture of teamwork to support the collective efficacy of staff to achieve equitable student outcomes. In order to do this effectively, leadership must first have an understanding and clear vision with goals and objectives for the culture of their school. Licata, Teddlie, and Greenfieed (1990) describe the vision as “the capacity to see the discrepancy between how things are and how they might be and the need to compel others to act on those imagined possibilities” (p.94). The leader must be intentional about shaping that vision of collaboration, and then nurturing the capacity of the adults in the school community to help shape that culture as well (Robbins & Finley, 2000). “Effective professional development is an invaluable way to benefit both the individual and the profession” (Battersby & Verdi, 2015, p.25). This can be achieved through collaboration, in a place where every team member understands they are accountable to the students, and each other, to achieve a culture of excellence schoolwide. The synergy of these elements come together to ultimately create a mature, high-functioning professional learning community.

Building a Collaborative Team

Just as leaders plan for the instructional success of students and ensure teachers have the necessary tools to implement the curriculum, leaders must also create a plan that defines the expected outcomes for team collaboration. In order to build buy-in, the leader must communicate ‘why’ the team must exist. The intellectual thought and productivity of the collective is so much more powerful than that of the individual. Each team will go through stages on their path to becoming a successful learning community. The stages of team development include: forming, norming, storming, performing, and adjourning (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977). During the forming, norming, and storming stages the team looks to the leader for direction and clarity around roles and responsibilities, collaboration parameters, and managing tension and conflict. Ultimately, the leader’s goal is to build a performing team with individuals who are committed to goals, display genuine interests in other members of the team, practice shared decision-making, take risks to contribute ideas, and provide essential feedback on team performance (Bryk, 2010). However, this does not happen without going through the storming stage where conflict, and oftentimes, confusion are present.

The leader can ensure the team sustains during the storming stage of conflict and confusion by forming dynamic groups where everyone is aware of each member’s strengths and potential limiters, by creating team ground rules or norms for working together, by focusing on skill development, and by building authentic relationships when the team is emerging. Without properly setting the stage during forming by monitoring how the team is functioning, giving individual members and the team feedback on their outputs and deepening skills, the team’s dysfunction will become its norm. The leader can build a strong foundation and look for signs of team dysfunction early. For instance, when the team does not demonstrate evidence of clear goals, work towards common outcomes and evidence of skill development this may be an indicator that a storm will begin to brew because the initial groundwork was not done during the forming stage.

How many times have leaders known teachers to articulate positive team dynamics, yet after observations the practice did not meet expectations?

When Deirdre first became a middle school principal, her goal was to establish professional learning communities on her campus. She envisioned a space where teachers would plan lessons, analyze data, learn instructional strategies and practice those strategies with protocols in order to obtain feedback from their peers. She quickly learned that clear communication about roles, responsibilities and outcomes and building capacity is vital for effective team dynamics. When she observed her teams early on teachers were not intentionally planning lessons as a team. There was not a strategic and beneficial process to analyze data to inform the practice. The process did not exemplify teamwork, but isolation in a group format. In order to ensure the emerging of a strong team, Deirdre spent time with teacher leaders supporting the development of team norms, a professional learning community calendar and outlining specific procedures for planning, looking at data and learning best instructional practices.

The leader must also be careful not to rely on a few members of the team to get tasks done. A culture of interdependence means everyone has a role and the leader has to utilize the strength of the collective. Focusing on the skills and capacity of a few team members leads to an environment of distrust. The leader should ensure accountability to each other and to the students becomes a norm.

As a campus leader, Kelly noticed the same math team teachers would be called upon to be in charge of leading the development of weekly lessons, develop assessments and attend trainings to bring new learning back to the team. These were teachers who had a history with the school and a track record of performance. However, she noticed the other members began to get disgruntled and would not actively participate in team meetings. The result was those not participating were disengaged and those who were participating in the process over time experienced burnout. As a result, Kelly had to take a step back to assess the strengths and limitations of the members of the team in order to build capacity across the team. This information was used to develop the professional learning calendar for the team. Each topic became a subject of development so the team could support one another in development of a new skill set.

The school will function better when the staff believes in the mission and in each other. Therefore, while the leader is elevating strengths, a process to address weaknesses must be implemented simultaneously. If staff does not have the skill to address the learning gaps, then leadership must provide opportunities to build teachers’ skill sets and thereby increase their efficacy. Every leader should develop a professional learning plan for each teacher to elevate their practice. This type of capacity building will sustain everyone on the team. The leader’s role then is to constantly revisit the team values of collaboration and interdependence as well as trust, accountability and vulnerability of teachers to rely on each other in order to fulfill the vision for the school.

Guiding the Forming Stage with Protocols

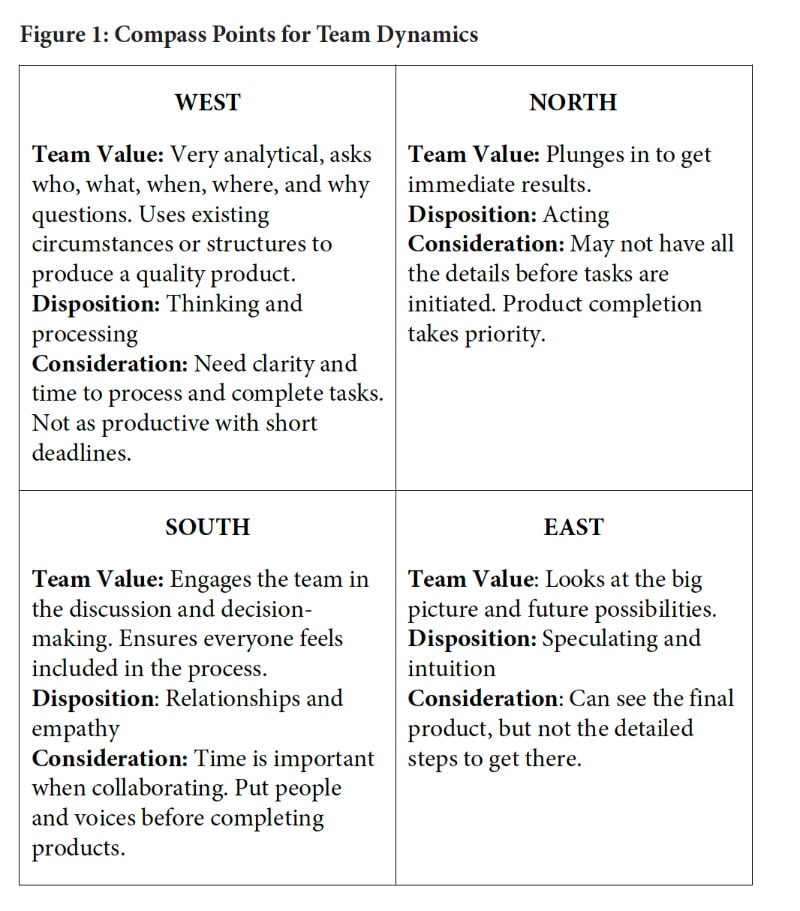

The members of the team have a dominant disposition that drives how they engage with others and how they make sense of the work to be done. Specifically, on any given team there may be individuals who pay attention to the details before beginning any task, and individuals who take into consideration all of the voices on the team before the work gets started. There will also be team members who want to plunge into the work immediately, and those who can see the bigger picture or the end goal of the work of the team. As the community emerges, the leader should use a structured process such as Compass Points: North, South, East, and West, a School Reform Initiative protocol developed by educators, to learn the disposition of each team member in order to capitalize on the value and potential limitations they bring to the learning community. See Figure 1 Compass Points for Team Dynamics for explanation of the different dispositions.

Establishing the preferences of the members of the team is only the first step to professional learning community forming or emerging stage. The leader must also work with the team to establish ground rules and to set goals and guidelines for checking on progress as the new learning community develops. Any given team in a school can expect that difficult issues or dilemmas will arise as the learning community works together over time.Creating ground rules or norms for collaboration builds trust, clarifies the group expectations of one another, and highlights points of reflection on practice for the team. The Attributes of a Learning Community Protocol is a useful process for leaders to establish norms and the guidelines for their learning community. In this protocol team members share personal experiences in previous teams where the collaboration was positive, productive, and had an intentional focus on learning for all. The characteristics that are shared by the members of the team become the measure by which the team will determine its effectiveness as a learning community.

Establishing the preferences of the members of the team is only the first step to professional learning community forming or emerging stage. The leader must also work with the team to establish ground rules and to set goals and guidelines for checking on progress as the new learning community develops. Any given team in a school can expect that difficult issues or dilemmas will arise as the learning community works together over time.Creating ground rules or norms for collaboration builds trust, clarifies the group expectations of one another, and highlights points of reflection on practice for the team. The Attributes of a Learning Community Protocol is a useful process for leaders to establish norms and the guidelines for their learning community. In this protocol team members share personal experiences in previous teams where the collaboration was positive, productive, and had an intentional focus on learning for all. The characteristics that are shared by the members of the team become the measure by which the team will determine its effectiveness as a learning community.

The role of the campus leader is to create an environment where teachers are able to work collaboratively to examine and reflect on their practice and learn from each other. When a culture of collaboration and interdependence is created equitable outcomes are achieved because teachers build their collective efficacy to implement practices that serve all children (Tschannen-Moran & Barr, 2004). The leader must also be intentional about setting the groundwork that will successfully move the team through the stages of team development. The foundational work is imperative to assess the dynamics and dispositions of the members of the team. Doing this early work prepares the team to navigate the storming stage and ultimately perform as a mature professional learning community.

References

Battersby, S. L. & Verdi, B. (2015). The Culture of Professional Learning Communities and Connections to Improve Teacher Efficacy and Support Student Learning. Arts Education Policy Review, 116(1), 22–29. https://doi-org.libproxy.lamar.edu/10.1080/10632913.2015.970096.

Brown, K. & Williams, D. (Feb. 2019). Equity Audits: A Powerful Tool to Transform Leading and Learning. Instructional Leader. Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association (TEPSA) Instructional Leader, 32(2), 1-5.

Bryk, A. S. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 91(7), 23-30. Retrieved from http://corvette.salemstate.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct= true&AuthType=cookie,ip,cpid&custid=ssc&db=eric&AN=EJ882366&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Fahey, K. & Ippolito, J. (2017). Towards a General Theory of SRI’s Intentional Learning Communities. Retrieved from The School Reform Initiative. https://www.schoolreforminitiative.org/research/general-theory-of-intentional-learning-communities/.

Licata, J. W., Teddlie, C. B., & Greenfield, W. D. (1990). Principal Vision, Teacher Sense of Autonomy, and Environmental Robustness. Journal of Educational Research, 84(2), 93–99. https://doi-org.libproxy.lamar.edu/10.1080/00220671.1990.10885998.

Marzano, R. J. (2013) The Marzano teacher evaluation model. Retrieved from http://www.marzanoresearch.com/hrs/leadershiptools/marzano-teacher-evaluation-model.

Mohr, N. & Dichter, A. (2001). Stages of Team Development: Lessons from the Struggles of Site-Based Management. Phi Delta Kappan. pp 1-14.

Robbins, H. & Finley, M. (2000). The New Why Teams Don’t Work. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler.

Ronfeldt, M. Farmer, S. McQueen, K. & Grisson, J. (2015). Teacher Collaboration in Instructional Teams and Student Achievement. American Educational Research Journal 52 (3), 475-514.

Thornburg, D. G., & Mungai, A. (2011). Teacher Empowerment and School Reform. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 5(4), 205–217. Retrieved from https://search-ebscohost-com.libproxy.lamar.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=65031234&site=ehost-live.

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. C. (1977). Stages of small-group development revisited. Group & Organizational Studies, 2, 419—427.

Tschannen-Moran, M. & Barr, M. (2004). Fostering Student Learning: The Relationship of Collective Teacher Efficacy and Student Achievement. Leadership and Policy in Schools 3(3), 189-209.

Williams, D., & Brown, K. (Jan. 2019). Equity: Buzzword or Bold Commitment to School Transformation. Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association (TEPSA).Instructional Leader. 32(1), 1-3.

Dr. Kelly Brown serves as an assistant professor of Educational Leadership in the Center for Doctoral Studies at Lamar University. She studies and researches issues regarding leadership and underserved populations. She has been a career educator and is an advocate for all students.

Dr. Deirdre Williams is the Executive Director for the School Reform Initiative, an independent nonprofit organization. She leads the work of serving thousands of educators throughout the U.S. to create transformational learning communities in schools committed to educational equity and excellence.

TEPSA Instructional Leader, May 2019, Vol 32, No 3

Copyright © 2019 by the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association. No part of articles in TEPSA publications or on the website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association.