By Kelly Brown, EdD and Deirdre Williams, EdD

This is part two in a three-part series on equity in education. In the first article, we explored how leaders can begin to use equity to transform the school environment for every learner.

Systemic equity encompasses the transformed ways in which schools operate to ensure every student, no matter the learning environment, is provided with the greatest opportunity to learn (Scott, 2001). When leaders are concerned about systemic equity, they focus not only on student academic achievement but also the quality of their teachers and instructional programs (Skrla, McKenzie, & Scheurich, 2009). These leaders ensure a skilled teacher is in every classroom so each student’s needs are met. They are also careful not to make assumptions that equitable practices are happening in their schools. Equity-conscious leaders collect evidence to confirm every member of the school community is willing to help all students achieve their highest potential. One useful strategy leaders can use to examine how systemic equity issues are operating in their schools is a campus-based equity audit (Brown, 2010).

Equity audits are a leadership tool used to collect the data that informs the process of removing programmatic barriers that impede full participation, access, and opportunity for all students to receive an equitable and excellent education. With this process, leaders can assess the extent to which equity is present in such areas as teacher quality, the overall instructional setting, and student achievement and attainment (Sparks, 2015). Equity audits support proactive leaders with assessing and planning for campus improvement that addresses the specific cultural, linguistic, socioeconomic, and racial dynamics present in the school community (Skrla et al., 2009).

According to the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA), campus leaders should have five major goals for achieving systemic equity (Scott, 2001). These goals include comparably high achievement and other student outcomes, equitable access and inclusion in the learning environment, equitable treatment of children and families, equitable opportunities to learn, and equitable resource distribution. While it may be overwhelming to address all five goals concurrently, using this information, leaders can prioritize and focus on implementation with fidelity until all goals are addressed. To be clear, the leader may begin with a prioritized goal, but a school will not achieve systemic equity until all five goals are addressed (Brown, 2010).

The previous article, “Equity: Buzzword or Bold Commitment to School Transformation” discussed how leaders can begin to use equity to transform the school environment for every learner (Williams & Brown, 2019). The equity audit is a systematic process to achieve that goal. While it can seem quite daunting for school leaders, this article offers four achievable action steps leaders can implement as they make their bold commitment to realize a sustainable transformation toward equity in their schools.

The leader will begin by conducting focused observations of classrooms, campus professional learning community sessions, and staff engagement with families during conferences and other events, to collect data related to staff practices and conversations. Next, the leader will begin analyzing the data collected from observations and juxtaposing that information with school programmatic data. During this step, leaders and school stakeholders get to take a deeper dive into understanding what the inequitable outcomes are and their root causes (Javius, 2017). Once everyone understands the data, it is time to plan and engage in campuswide professional learning that will support implementation of action steps toward achieving systemic equity goals. Finally, the most important action of the equity auditing process is reflection, specifically, on ways in which inequitable practices are perpetuated in the school.

Conduct Equity Focused Observations

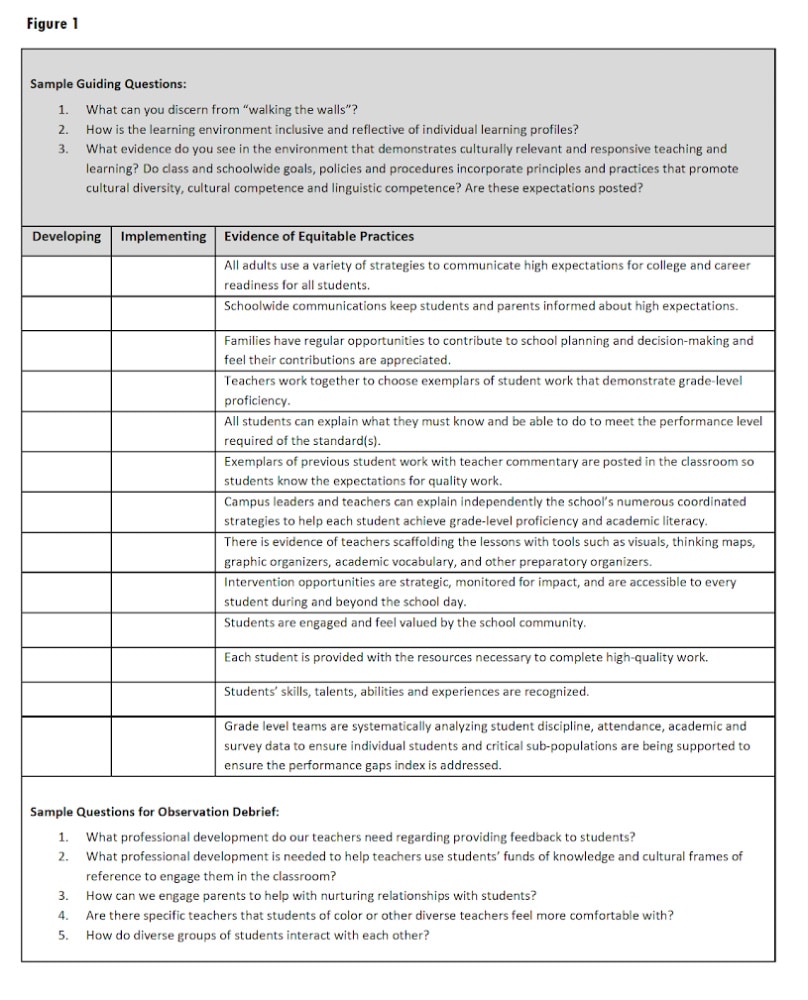

The first step is to conduct focused observations of classrooms, campus professional learning community sessions, and staff engagement with families during conferences and other events to collect data related to staff practices and conversations. Any successful change toward high achievement for all learners will begin with campus observations that have a specific focus of inquiry to drive targeted data collection based on equity goals. While a narrow set of questions will be developed to help focus the observations, the major question leaders should consider is: To what extent do the practices and discourse held in our school provide each student with the greatest opportunity to learn? Figure 1 on page 3, represents an example of some of the equitable practices, guiding questions, and follow-up dialogue questions the audit team might consider during step one of the process.

It is expected step one will be completed by a team of school stakeholders so quality equity-centered debriefs can occur (Skrla et al., 2009). Conducting observations through an equity lens allows educators to have a more comprehensive view of teacher practices on the campus. The auditing team should discuss observations and co-create meaning that will later inform individual coaching, collaborative professional learning, and campus growth toward equity. This practice builds synergy, cohesion and becomes an opportunity for transformation of the team.

Mine the Data

The second step involved in an equity audit is to analyze and understand the data collected. The team should utilize the observation data previously collected and juxtapose it with other sources of school data, including the school performance data; discipline data, and programmatic data such as special education, gifted and talented, bilingual/ELL education, attendance, and parental empowerment (Lashley & Stickl, 2016). It is important for leaders to use the data to earnestly understand how the practices and beliefs of the school community perpetuate gaps in student outcomes. With the equity audit, the seen and unseen implications of practices and beliefs with respect to race, culture, language, socioeconomic status, and the academic realities on campus can be addressed. Aligning those practices and beliefs to support the social, emotional, and academic achievement of each child is paramount if educators are to move toward systemic equity.

Often, a correlation exists between educators struggling to make cultural connections with their students and how those students perform academically (Akrzewski, 2012; Valenzuela, 1999). Trends in the academic data can highlight the curricular and instructional gaps as well as inform teachers on what they need to learn and be able to do to support student growth. Some questions for leaders and teachers to consider are:

- Which groups of students are served well academically by our current practices?

- Which groups of students are not being served well academically by our current practices?

- How can we ensure more equitable practices on our campus so every student is served well?

- What is the connection between the professional learning needs of the teacher and the learning outcomes of the students?

Once the data has been collected, the leadership team can begin to make sense of the data using a protocol such as the Atlas Looking at Data developed by the School Reform Initiative. Having this structured conversation about the data will surface the implications and recommendations for leadership practice. The process of analyzing the data begins to tell the school’s story because it will underscore the impact on children being served, including the children who are disproportionately affected by the school’s current practices. It is important to understand the impact school practices have on all children. However, to achieve systemic equity, leaders must target their actions toward practices that disproportionately hinder the progress of specific groups.

Utilizing the triangulation of teacher quality, programmatic, and student achievement data provides greater insight to realizing campus issues so they can be addressed (Lashley & Stickl, 2016). As the leadership team works to confront equity issues, the team must clarify the level at which they should focus on the issue. Specifically, does the data uncover systemic issues that must be addressed at the leadership level, or can the issues be resolved by change in individual teacher mindset and practice (Javius, 2017)?

Lead Equity-Conscious Professional Learning

Leaders must focus professional learning time to address equity goals consistently so discussions become a part of how teachers view data, curriculum, and daily instructional practices. Without taking the time to build capacity and buy-in from the staff, substantive changes will be short lived. The specific learning opportunities, especially those dealing with race and culture, should be done in a safe and supportive learning community and be focused on strategies and beliefs. The time spent in professional learning is the key to the transformation process that will build equity. Transformative learning, according to Mezirow (1990), is “the process of learning through critical self-reflection, which results in the reformulation of a ‘meaning perspective’ to allow a more inclusive, discriminating, and integrative understanding of experience. Learning includes acting on these insights” (p. xii).

Based on the discussions from the observations, the team will decide what actions will begin a transformation of the mindsets of teachers and the capacity to enact practices that will yield equitable outcomes. The transformative learning process is the entry point for leaders to begin dialogue that includes a “critical examination of assumptions or meaning perspectives, underpinning deep-rooted value judgements and expectations” (Cox, 2015, p. 27). This also means leaders will differentiate adult learning experiences and protocols to structure reflective discourse based on where teachers are in their equity consciousness journey so the work is conducted in a safe and supportive environment. Leaders should develop a professional learning calendar that incorporates opportunities for staff to develop equity-centered curriculum, learn equity-conscious strategies for instructional delivery and community building, practice those strategies with their peers, and analyze campus instructional and cultural data with an equity mindset.

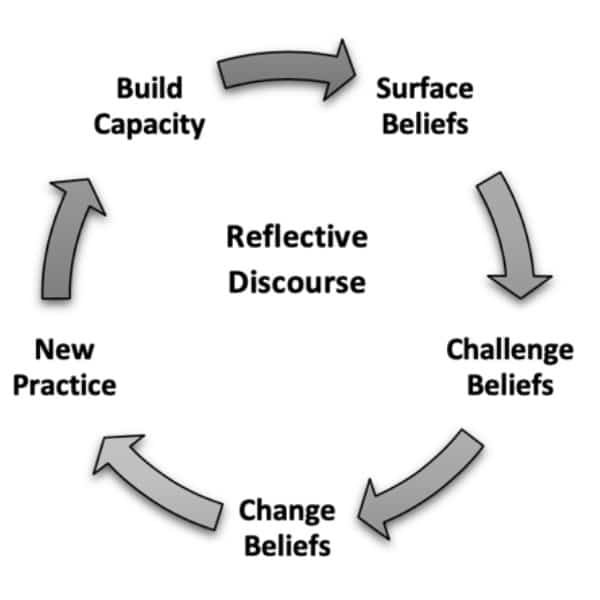

A constructivist approach to the professional learning process is vital for teachers to understand the need for growth in their practice (Cox, 2015). The relevance of the learning is crucial, and this allows leaders to tap into the internal motivation of staff to produce better outcomes for all students. Utilizing structured protocols to guide reflection and understanding helps teachers make connections between their previous experiences and their current practices, which then impacts student achievement. This creates the motivation for teachers to try new practices, not out of compliance but because they believe the practices will have a sustainable impact on teaching and learning. The figure above highlights the process teachers should be guided through in order to achieve a mindset shift toward equity. Connecting the data from the previous steps highlights where staff may need support to move through the cycle of transformational professional learning to adapt to equity growth systems.

The cycle of development should occur through a process of reflective discourse guided by structured conversations and be done in a safe and supportive environment. Surfacing and challenging beliefs around such constructs as implicit bias and positionality support the teacher’s ability to build authentic relationships with children. The discourse also guides teachers in changing beliefs around equity gaps through observation of data and reflection of current classroom practices. Finally, teachers should practice new skills regularly to build capacity through team engagement, support, and accountability. The leadership team understands teachers will move through the process in such a way that they are supported to feel comfortable in the risk zone where new learning happens.

Reflect on Equity Auditing Process

The leadership team is seeking to create a transformative learning environment for teachers and students, but at the same time, the process is also transformative for the team. A fierce commitment to equity means that, at every level and phase, critical reflection of the staff’s “why” for pursuing equity and their “how” should occur (Javius, 2017). Critical reflection helps the team derive meaning from each of the experiences. These reflections can become school case studies for staff to constantly refer to during professional learning time as they refine their instructional practices. Reflection also allows the audit team to evaluate the impact of changes being implemented. Specifically, the audit team as well as the teachers in professional learning time will constantly evaluate how practices that have been implemented support progress toward equity goals and the extent to which they will yield sustainable change.

The promotion of educational equity is a complex issue (Skrla et al., 2009). Research has shown the importance of school-based learning for students of color and students from poverty. These students have experienced education in schools with inequitable systems and practices for years. Now is the time for educational professionals to work with a sense of urgency and implement practices that will support equitable treatment and outcomes for each learner. An audit process will identify inequitable practices and create a plan to ensure every student has access to the curriculum, assessment, pedagogy, and challenge they need based on the recognition and response to their individual differences, and the sociopolitical context of teaching and learning. This will put our educational system on the right track (National Association for Multicultural Education, 2019).

References

References

Akrzewski, V. (2012, September 18). Four ways teachers can show they care. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/caring_teacher_student_relationship.

Brown, K. M. (2010). Schools of excellence AND equity? Using equity audits as a tool to expose a flawed system of recognition. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 5(5), 1-12. doi:10.22230/ijepl.2010v5n5a206.

Cox, E. (2015). Coaching and adult learning: Theory and practice. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 2015(148), 27-38. doi:10.1002/ace.20149.

Javius, E. L. (2017). Educational equity is about more than closing gaps. Leadership, 46(5), 18-22. Retrieved from https://libproxy.lamar.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com /login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=123010750&site=ehost-live.

Lashley, C. A. & Stickl, J. (2016). Counselors and principals: Collaborating to improve instructional equity. Journal of Organizational and Educational Leadership, 2(1). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1131520.pdf.

Mezirow, J. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

National Association for Multicultural Education. (n.d.). What is equity? Retrieved from https://www.nameorg.org/learn/what_is_equity.php.

Scott, B. (2001, March). Coming of age. IDRA Newsletter. Retrieved from https://www.idra .org/resource-center/coming-of-age/.

Skrla, L., McKenzie, K. B. & Scheurich, J. J. (2009). Using equity audits to create equitable and excellent schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Sparks, S. D. (2015, September 17). How does an equity audit work? Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/inside-school-research/2015/09 /how_does_an_equity_audit_work.html.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Williams, D. & Brown, K. (2019). Equity: Buzzword or bold commitment to school transformation. Instructional Leader, 32(1), 1-3. Retrieved from https://www.schoolreforminitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Williams-and-Brown-Equity-Article-January-2019-ILN-1.pdf.

Dr. Kelly Brown serves as an assistant professor of Educational Leadership in the Center for Doctoral Studies at Lamar University. She studies and researches issues regarding leadership and underserved populations. She has been a career educator and is an advocate for all students.

Dr. Deirdre Williams is the Executive Director for the School Reform Initiative, an independent nonprofit organization. She leads the work of serving thousands of educators throughout the U.S. to create transformational learning communities in schools committed to educational equity and excellence.

TEPSA Instructional Leader, March 2019, Vol 32, No 2

Copyright © 2019 by the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association. No part of articles in TEPSA publications or on the website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association.