By Barbara R. Blackburn, PhD and Ronald Williamson, EdD

Gone are the days of the solitary teacher working in isolation with their own set of students. That model has been replaced by a more collaborative environment where teachers are expected to work together to improve instruction, and where that interaction provides some of the richest and most valuable professional development available.

A central feature in many schools is instructional coaching where teachers work with a coach to analyze their instructional practices and develop strategies to enhance and improve their teaching. Instructional coaching has emerged as a powerful tool. One study (Kraft & Blazar, 2018) found teachers who worked with an instructional coach displayed greater effectiveness equivalent to the difference between a novice teacher and a teacher with five to 10 years of experience.

Instructional Coaching: The Past

Where does the concept of instructional coaching come from? Although there have been sporadic, isolated instances of coaches prior to the 1980s, the work of Bruce Joyce and Beverly Showers on peer coaching in the 1980s provided the foundation of what we use as instructional coaching today. In the 1990s funding for literacy coaches through the Reading Excellence Act broadened interest in coaching. The No Child Left Behind Act (2001) expanded the use of coaching, especially literacy coaching when paired with programs such as Success for All and America’s Choice. Through the 1990s and 2000s, coaching spread to other content areas, especially math and science. Many districts also hired general instructional coaches who worked with multiple subject areas. No matter the subject, the focus was generally on improving student learning through improving teacher practice.

Instructional Coaching: The Present

Now, instructional coaching is a core part of many schools. It has become particularly important with the number of new, substitute, and non-traditional teachers, the increasing social-emotional needs of students, and the continuing academic gaps since COVID.

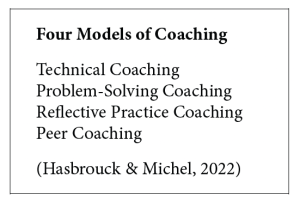

Let’s look at four common models of coaching.

In technical coaching, the coaching process occurs when teachers are implementing a specific plan or program. Coaching activities are focused on how teachers can best utilize the program. Problem-solving coaching focuses on a specific concern that a teacher identified, such as instructional pacing. With reflective coaching, the emphasis shifts to facilitating teachers’ thought processing and decision making. One of the most popular models for this is Cognitive Coaching by Arthur L. Costa and Robert J. Garmston (2015). Peer coaching, a popular choice, was pioneered by Joyce and Showers (2002). They cautioned that during peer coaching teachers should simply provide feedback rather than morphing into supervision.

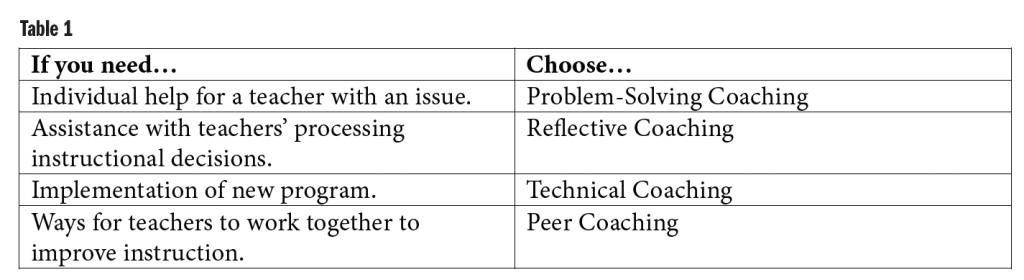

There are other variations in schools, but these four provide the framework for instructional coaching. How do you know what to use? Consider your teachers and your students, and then choose based on what best meets your needs. See table 1 below.

Instructional Coaching: The Future

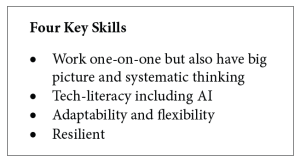

In the future, schools will likely change in ways we cannot anticipate. The growth of AI, political pressures, changing societal needs, and evolving needs of teachers and students will all impact the future design of instructional coaching. Although we cannot describe what the perfect coaching role will look like in 20 years, there are some skills we believe will be needed by successful coaches.

First, although working with teachers one-on-one will remain an important part of the coach’s role, it will be critical for coaches to integrate their work into the big picture of the school and district. Systematic thinking or seeing how all parts of the overall system work together is part of seeing the big picture.

Frequently, instructional coaching is implemented with a focus on one specific need like improved reading instruction. Often what occurs is the instructional strategies useful in reading may prove adaptable and useful in other content areas as well. A systemic approach recognizes that effective instruction is not limited. It also recognizes that teachers will have varied needs and thus, the focus will be different for each teacher working with an instructional coach.

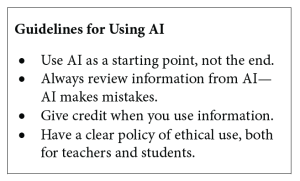

Next, coaches must not only use technology but utilize it in ways that enhances their work. This includes artificial intelligence. While AI is continually emerging technology, coaches will need to find effective, ethical ways to use AI to help teachers improve their practice. This might include helping teachers understand that simply pulling lesson plans from AI isn’t best practice. However, helping teachers use AI to generate starting points for lesson planning, while retaining human control by adapting the lessons to best meet students’ needs, is a strong alternative.

Third, coaches must be adaptable and flexible. Education and our knowledge of effective instruction continues to evolve, and instructional coaching must adapt as well. We spoke with one coach whose role has shifted in the last few years. Her school hired several new teachers under emergency certification—teachers not trained in a traditional way. Her coaching knowledge and methods assumed teachers had a base level of knowledge, something which was not true with these new teachers. In what she called “the biggest challenge of my life,” she had to revise her view of teacher preparation to appropriately support her new teachers. Adaptability and flexibility were critical.

Finally, coaches for the future will need to be resilient. They will need to face a myriad of challenges we are unable to anticipate, find ways to address those challenges, and bounce back after any setbacks. The coach we described in the previous section is a testament to resilience. Before she learned to adapt, she faced multiple obstacles: her own viewpoint of teacher preparation, the lack of background knowledge of the emergency teachers, and the different perspective of new teachers.

An example demonstrates the importance of resilience. One of her teachers was resistant to small group instruction. The coach explained the importance of groups and helped him develop lesson plans that incorporated groups. The teacher continued to oppose the idea. Barbara was visiting the school, and met with the teacher. She discovered that, as a former manager in a textile mill, he was used to telling groups what to do. That direct approach didn’t work well with middle school students. He was nervous that if he incorporated small groups he would lose control of his classroom and administrators would think he was a bad teacher. Once I shared this information with the coach, she modified her approach—providing extra help to monitor the groups until he became comfortable with the approach. The coach felt like a failure, but when he thanked her for her help, she realized the need to always adapt and be flexible in her coaching. Resiliency is critical for future success.

A Final Note

Instructional coaching is a proven tool for improving teaching and student learning. As the needs of students and teachers change, the role of instructional coach needs to change. Effective coaches recognize the need to be flexible and adapt their work to specific teachers rather than embrace a “one size fits all” approach. Aligning the approach with the need is critical to success.

Dr. Barbara R. Blackburn, a Top 10 Global Guru, is a best-selling author of more than 30 books, including the bestseller Rigor is NOT a Four-Letter Word, Rigor for Students with Special Needs, Rigor in Your School; 7 Strategies for Improving Your School, and Improving Teacher Morale and Motivation. Learn more at www.barbarablackburnonline.com.

Dr. Ronald Williamson is Professor Emeritus of Educational Leadership at Eastern Michigan University. He is a former principal, central office administrator and Executive Director of National Middle School Association (now AMLE).

References

Costa, A. & Garmston, R. (2002). Cognitive Coaching: A Foundation for Renaissance Schools. New York: Rowan & Littlefield.

Hasbrouck, J. & Michel, D. (2022). Student-focused coaching. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Kraft, M & Blazar, D. (2018). Taking teacher coaching to scale. Education Next, 18(4). Retrieved online July 5, 2025 at https://www.educationnext.org/taking-teacher-coaching-to-scale-can-personalized-training-become-standard-practice/

Joyce, B. & Showers, B. (2002). Designing training and peer coaching. Alexandria, VA; ASCD.

TEPSA News, January/February 2026, Vol 83, No 1

Copyright © 2026 by the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association. No part of articles in TEPSA publications or on the website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association.