By Rachel Taylor, EdD

When two principals come together to discuss their experiences as principals and one likens the job to hanging off a cliff and the other says it is like living in a swirling tornado, you better believe the work must have its challenges. How do we ensure these principals persist in their important work of leading our schools and grow in their capacities to handle the challenges of the role?

Principal resilience and persistence matter. As a principal I found myself overwhelmed by the internal and external forces preventing me from being the instructional leader I desired to be. My struggle to balance my professional responsibilities made it difficult to leave my school office and caused me to feel inadequate for the key task of impacting student learning. The tipping point occurred when, after being a principal for several years, I had my first child. I struggled to see how I could juggle being a mother and an effective principal at the same time. So I decided to stop serving as a principal and instead to stay at home with my children. This experience caused me to wonder how other principals persist in their roles, and thus created a desire to explore principal development that supports and impacts the persistence of school leaders. As a result, I returned to school. At every turn I studied the principalship.

How do principals persist amidst the myriad of responsibilities that surround them?

What are the major barriers in the principalship?

What are the behaviors of principals who have persisted in the principalship?

Today’s modern principals have increased expectations and standards for student achievement yet they press on, and I wanted to know how they persist.

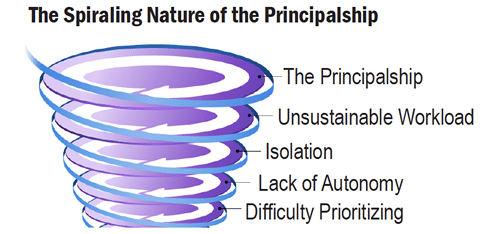

After interviewing and examining the experiences of 10 people who have worked five or more years in the principalship, four major themes emerged as barriers to principal persistence:

- Unsustainable workload

- Lack of autonomy

- Isolation

- Difficulty prioritizing

As an illustration, imagine the principalship as a tornado. A principal enters the tornado and quickly feels the workload is unsustainable, there is a lack of autonomy, the role is isolated, and prioritizing is difficult. What should one tackle first when everything is swirling? Add to this the disparity between how a principal feels and how the principal perceives other principals are handling their own tornado and you have a recipe for loneliness and isolation.

While the illustration of the tornado is fictional, there is a real feeling in the principalship of, “Will these winds ever subside?” Does the tornado ever end or, at least, slow down over time (experience), or do principals actually grow stronger and grow in their ability to withstand the swirling winds (grow their leadership capacity)? Perhaps there is a combination of settling winds over time (experience) and gained strength (leadership capacity) the longer a principal endures the tornado’s churn.

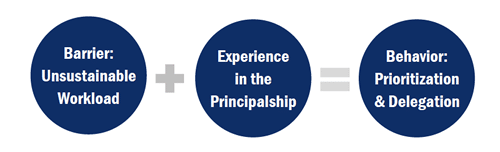

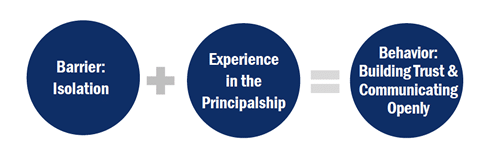

My study of the 10 principals led me to conclude that the barriers principals repeatedly encounter in the principalship actually generate behaviors that continue to get better over time and ultimately lead to sustainability and persistence in the role. What are those behaviors?

Barrier of Unsustainable Workload

A principal’s attempt to satisfy the many demands from various stakeholders amidst the principal’s myriad of responsibilities can be quite daunting and, frankly, draining. One principal summed it up, “It’s about students and sometimes we get caught up with an angry parent, we get caught up with a lack of funding, or we get caught up with state testing. There are so many things that can interrupt the work we do, and take us off the path and demand our time.” Over time though, a principal’s workload becomes more manageable as that principal persists for multiple years and learns behaviors like prioritizing and delegating tasks.

Barrier of Principal Isolation

There is isolation in the principalship because no one else in the school experiences a principal’s level of responsibility. Most schools employ only one principal. There is also isolation in not feeling directly or overtly involved in the success of the campus. Additionally, there is an uncertainty of what it is exactly one should be doing each day to maximize one’s impact on the campus. Furthermore, the looming ambiguity that other principals, in the same position, may not be struggling makes the job feel lonely. One principal explained, “Being a principal is a lonely job because nobody understands it. You cannot complain to your teachers. Nobody gets it—you’re the lone ranger and it can be lonely.” Also supporting the theme of isolation is one principal’s statement, “We’ve got health issues; we’ve got family issues and it’s heavy stuff and there’s so much that you carry that nobody else knows.” Thankfully, as a principal becomes more experienced, he/she learns behaviors such as building trust and communicating openly to help overcome the barrier of isolation.

With time and with experience, persisting becomes easier because behaviors are formed that help principals overcome the barriers in the role. Put simply, the longer a principal persists the more likely the principal is to demonstrate positive behaviors and attributes that are associated with the more experienced principals in the district, such as:

- Building relationships

- Prioritization and delegation

- Communication

My study was unique. Many other studies point to why principals leave the principalship. I wanted to know why principals stay in the principalship. I found the principals who persist are the ones who are good at and value relationships, understand how to prioritize effectively, and are strong communicators. My findings suggest there is staying power by persisting in the principalship.

School District Support

Importantly, based on my study I recommend school districts acknowledge the importance of principals persisting for five years and target professional development based on experience to send the message the principalship actually becomes more do-able over time—the enormity of the principalship role shrinks when longevity grows. Imagine if school districts designed, with intentionality, development for principals based on their experience level with consideration of barriers in the principalship as well as emergent behaviors of principals who have persisted over time. There are important implications for training aspiring principals, principals, supervisors, and superintendents. Put simply, the longer a principal persists in a district the more likely the principal is to demonstrate positive behaviors and attributes that are associated with the more experienced principals in the district.

So how should districts implement this type of professional development? Start with a new vision. The new vision is a methodical way of training aspiring leaders, inexperienced principals, and experienced principals to ensure principals persist in the principalship, with confidence, year after year. Next, consider the resources available to attain this vision. A district’s central office leadership team can define, imagine, make, and test possible solutions to principal persistence by tapping into the wonderful wealth of knowledge they have at their fingertips: the district’s principals. Adjusting a principal’s experience by applying the insight of his or her peers is highly impactful.

In terms of rollout, the professional development initiative I suggest is one that can be piloted on first year principals, redesigned, and then applied at the next level: first year principals and principals with one to three years of experience. Next, the initiative can be further redesigned and then applied to multiple principals across various years of experience. After multiple tweaks and iterations, the professional development initiative may be applied to an entire district of school leaders. Thus, the vision for this professional development initiative is to intentionally create thoughtful and methodical ways of training aspiring leaders, inexperienced principals, and experienced principals to ensure that principal training and development produces principals who persist, with confidence, year after year by highlighting the behaviors principals develop over time to deal with the demands of the principalship.

In sum, school districts should address the barriers principals face in their early years of development (unsustainable workload, lack of autonomy, isolation, and difficulty prioritizing) and highlight impactful learned behaviors such as building trust with stakeholders, better prioritizing responsibilities, and allowing communication to become more open, clear, and positive. To do so, school districts should design, with intentionality, professional development for principals based on their experience level. My study suggests these districts may increase the likelihood their principals will persist over time in their roles.

Dr. Rachel Taylor is a former teacher in Galena Park ISD and former principal in Frisco ISD. She completed her doctoral studies at SMU. Rachel has a heart for school leaders and their impact on Texas students. She is currently a consultant at Fringe Learning.

TEPSA Leader, Fall 2019, Vol 32, No 5

Copyright © 2019 by the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association. No part of articles in TEPSA publications or on the website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the Texas Elementary Principals and Supervisors Association.